Story by Editor-at-Large CAROLINA OGLIARO

Shattering Perceptions: Simon Berger and the Alchemy of Glass in “A Matter of Metamorphosis

In the hushed dialogue between fragility and force, few artists have learned to speak as eloquently as Simon Berger. Known internationally for his hauntingly precise technique of sculpting portraits from shattered glass, Berger has elevated what is typically seen as destruction into a transcendent act of creation. With the highly anticipated site-specific exhibition A Matter of Metamorphosis, hosted at the Sala Espositiva del Comune di Casarsa della Delizia from April 12 to July 27, 2025, Berger plunges deeper than ever into the existential cracks of the human condition, guided by the spirits of two literary titans: Pier Paolo Pasolini and Franz Kafka.

This major solo exhibition is more than a display of technical virtuosity, it’s a metaphysical stage. Commissioned on the 50th anniversary of Pasolini’s death, and conceived as part of the cultural initiative TrasformARTI: L’arte come strumento per immaginare il futuro, the project is a collaboration between the Comune di Casarsa, Cris Contini Contemporary, and several regional institutions. At the heart of Berger’s contribution is an immersive installation that engages themes of metamorphosis, alienation, identity, and inner fracture, echoes of Kafka’s existentialism and Pasolini’s unflinching gaze on society.

A vital partner in bringing this visionary project to life, Cris Contini Contemporary has long championed artists who challenge traditional modes of expression and redefine the boundaries between form and philosophy. With galleries in London and Porto Montenegro, the gallery is internationally recognized for its curatorial focus on contemporary artists who explore social, spiritual, and psychological narratives through innovative materials. Under the guidance of curators Cristian and Maria Lucia Contini, the gallery continues to forge meaningful connections between artists and institutions, nurturing cross-disciplinary dialogues like this one, where art becomes both mirror and oracle.

Inside the exhibition, viewers are invited into a mirrored choreography of reflection and rupture. Six freestanding glass panels form a sacred circle, each etched with eyeless human faces, eerily spectral, suspended in an almost monastic silence. Discarded televisions, relics of a past obsessed with connectivity, lie dormant, their blank screens both witness and warning. The absence of visible eyes becomes an allegory for a society increasingly disconnected from authentic perception.

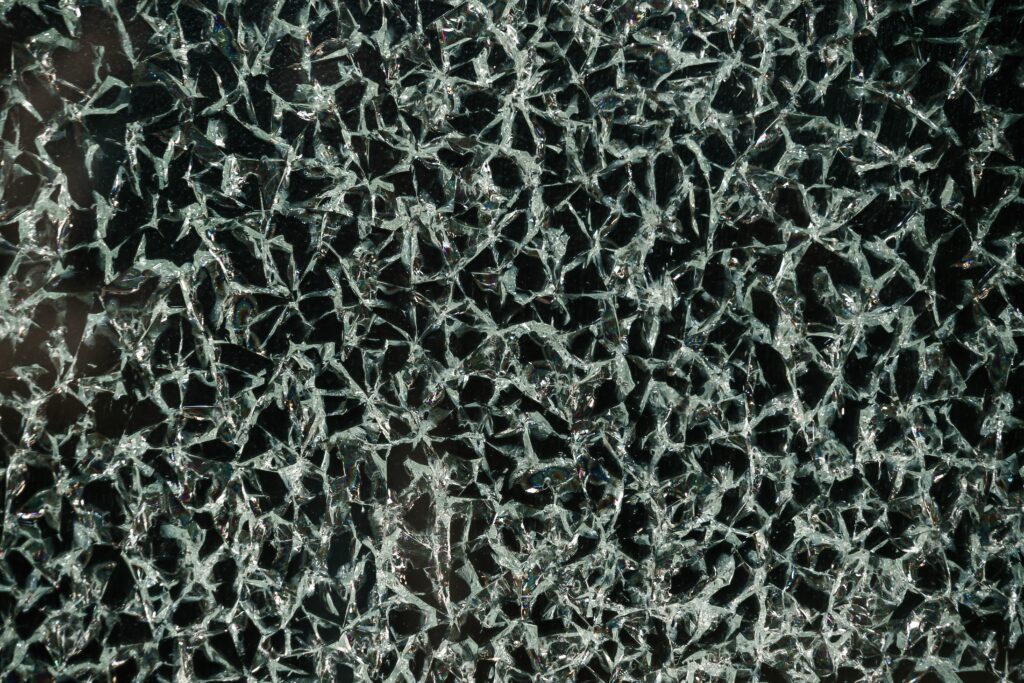

Berger’s technique, a ballet of hammer and breath, is singular. Each blow to the glass is an intentional incision, a philosophical act. In his hands, trauma becomes linework. The closer the strikes, the deeper the emotional texture. The fractures do not weaken the material, they animate it. Light filters through the fissures, refracting into ever-shifting portraits that seem to oscillate between apparition and presence. The result is not just art. It is an epiphany.

In homage to Pasolini, Berger has also gifted the city of Casarsa with a powerful piece: an eye of the poet carved into glass, piercing, omniscient, and disturbingly tender. This symbolic act of restitution reminds us that artists like Pasolini and Berger are united by their courage to see what others look away from and to transmute discomfort into beauty.

In the following conversation, Simon Berger opens up about the invisible threads connecting literature and material, trauma and transformation. We delve into his conceptual process, his fascination with faces, and the dance between chaos and control that defines his unique artistic vocabulary. Whether you are a seasoned collector or a curious soul encountering his work for the first time, prepare to see through the glass, and into yourself.

Glass, in its fragility and resilience, seems to serve as a metaphor for the human condition. What new insights about human nature do you discover each time you strike a glass sheet?

Working primordially with human faces, I aim to capture the character, appearance, and personality of the individual being in front of me. Each stroke thus comes as an exploration into the moods, hopes, dreams and expectations all of us carry within – the very concerns that motivate and drive us as we move through life. In its ambiguous nature, glass constitutes an ideal material to address and render the human condition in its many dimensions. In a world of incessant and accelerated change, creating art and (re)searching what truly defines us as a species allows me to continuously tease out new facets of what it means to be human – while also realising that fundamentally, across time and space, there is more that actually unites than what divides us. This is one of the messages I would like to share through my art – a beacon of hope in times of uncertainty.

The exhibition takes place in Casarsa della Delizia, a city closely linked to Pier Paolo Pasolini. How has Pasolini’s figure influenced or inspired the works presented in this exhibition? Similarly, your works evoke a sense of disconnection and alienation, themes also present in the literature of Franz Kafka. In what way has Kafka’s writing influenced your work?

Influential as both an artist and a political figure, Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s legacy continues to resonate through Italian culture. His unwavering dedication to diverse causes comes as an inspiration and prompt —especially in an age where old certainties are dissolved and whose new pace we are still trying to fully understand.

Similar circumstances characterised the years Pier Paolo Pasolini was active – if we think of the student movements of the 1960s and 1970s – and so I think that it is by turning to history that we can learn for an active making and shaping of the future. In this context I see a connection to Franz Kafka‘s writings. The uncanny settings the Austrian-Czech writer evoked in his short stories and novels speak to a current status quo where a sense of accelerated time, perpetual change and technological inventions has resulted in such phenomena as anxiety, uncertainty and desolation in the wake of a future seemingly out of our control.

Through works like Metamorphosis or The Process, Kafka rendered a similar state of alienation and disconnection which is why his oeuvre remains of such impact today.

Your creative process involves destruction to ultimately construct an image. What does this dynamic teach you about the nature of art and life?

While the creation of something new – and potentially beautiful – through destruction constitutes one of the defining traits of my art, it is in fact the very physical act and force of a hammer striking glass which continue to fascinate me. Watching the cracks in the pane form into meaningful patterns comes as a somewhat miraculous process that has never ceased to exert great intrigue. Similarly, it is upon moving through life that we wish for the sometimes seemingly loose strands to form into a narrative or image for this matter. My art may thus provide an analogy for the dynamics underlying and driving our existence towards the individual portraits we all are.

The title of your exhibition, “A Matter of Metamorphosis,” suggests a continuous state of becoming. How have you interpreted the concept of metamorphosis in the works on display, and what connection does it have to your artistic evolution?

The title A Matter of Metamorphosis was an attempt to bring together Kafka‘s eminent short story and the preferred medium of my art, glass. In a semantic play, the aim was thus to combine both. ‘Matter‘ is understood as an issue or concern, but also as the actual material used for the creation of the artworks. As Kafka‘s protagonist Gregor Samsa finds himself transformed upon waking up one morning, so does my art move through a gradual transformation of and on the glass pane. Whereas the main character in Kafka’s short story however experiences a cycle of decline, my art comes alive in an antithetical process with each stroke of the hammer breathing in a spirit and a soul.

Kafka and Pasolini explored themes of alienation and transformation. How have you translated these themes into the language of glass for this exhibition?

Upon entering the exhibition space, the beholders will encounter a site specific installation of dysfunct televisions that piled up in the centre emit nothing but the blank stare of faceless eyes. In an age that has been defined as ‘liquid modernity‘, most certainties have been dissolved, vanishing into the ether of time.

With the advent of technological devices such as smartphones and other gadgets, communication has been deferred and shifted to now (largely) happen in a virtual realm. Glass, in its multi-faceted nature and appearance, to me, constitutes the perfect medium to render this current tendency. Transparent and translucent, it affords two ways of looking at and through, thus causing the image to hover in a strange in-betweenness. A certain ‘limbo state‘ we all experience on a daily basis. At the same time, I find that glass -for these precise reasons – harbours a certain depth, a ‘virtuality‘ that can allude to alienation and estrangement as our gaze ‘disappears‘ in the medium.

Is there a precise moment in the creative process when you feel that the artwork “comes to life” and becomes something more than just an image?

In fact, there is. When kneeling over the glass pane, I watch the cracks form into images – that more than mere depictions of faces are traces of expressions where the character of an individual takes literal shape. As the tangle of breakages gradually reveals the person behind this ‘vitreous morphology‘ to me, I sense that the artwork ‘comes to life‘. In a way, every stroke with the hammer thus translates into breathing ‘spirit‘ and ‘soul‘ into the image.

The sound of the hammer striking the glass is an integral part of the creation process. How do you experience the physical and auditory aspects of your work as you create it?

During those moments when I find myself immersed in the creative process, the world around me ceases to exist. My focus is then on the artwork alone – the slow emergence of an image. It is a very introspective, perhaps even meditative state, as any noise or sound does not really reach me. All my attention is directed towards the image between the cracks and the glass pane. And while the realization of the works implies me in physical ways, I don‘t feel any of the strain or exertion – both might sometimes only come later.

Creating art from such an ephemeral material is also an act of accepting impermanence. How do you relate to the idea that your works might change over time?

For once, the works don‘t really change; the moment I‘ve settled on the final blow they remain the same. Change as such, however, in my eyes, is part of life. We might not always want it — but we simply need to accept it in order to find strategies of coping.

During the exhibition, an immersive installation featuring glass panels and decommissioned television screens will be presented. What is the significance of this installation, and what do you hope the audience will take away from it?

With the installation of discarded televisions and the void pairs of eyes staring back from them, I aim to challenge the audience to critically rethink our current status quo. Communication technology has brought us many advantages as we can now be in touch with people around the world, irrespective of geographic or temporal distances. At the same time, however, the transition from IRL (in real life) to URL has conferred a degree of virtuality, reducing and confining human interaction to the flat surface of a screen. Alienation and estrangement are two of the results -with consequences for how we live our relationships. The potential risks of this ‘metamorphosis‘ are what I want to highlight with my exhibition in Casarsa – with the hope of encouraging people to go out and bond as we used to for centuries.

Glass, with its fractures and transparency, creates a unique dialogue between the visible and the invisible. How important is what remains hidden compared to what emerges in your works?

In my eyes, great art lives through the tensions it alludes to and it harnesses. By bringing together the mutually exclusive, a realm of possibility opens up – to ponder, to reflect, to think anew. On these grounds, it is less a question of ultimately revealing or ultimately concealing – but rather, quite literally, striking a balance between both. My aim is therefore to invite the audience to come and discover for themselves. And in this regard, I believe art history has taught us that it is the unresolved that continues to excite, bedazzle and intrigue.

Simon Berger does not simply sculpt glass, he sculpts perception. In a world increasingly drawn to noise, speed, and superficiality, his work invites us to pause, reflect, and embrace the delicate beauty in what is broken. A Matter of Metamorphosis is a journey through the fragility of identity, the layers of existence, and the resilience that hides behind each fracture. It’s a psychological excavation, a communion with the unseen, and a mirror held up to a society unsure of its own reflection.

With the visionary support of Cris Contini Contemporary, whose curatorial direction continues to push the boundaries between the classic and the cutting edge, this exhibition is more than an artistic showcase, it is a living, breathing conversation about the evolution of human consciousness through art. Their commitment to showcasing boundary-defying artists like Berger is shaping the cultural landscape into one where innovation meets introspection.

Berger’s technique, a choreography of control and chaos, draws us in not just to admire but to feel, to question, to confront. His works, suspended between fragility and strength, speak of the human condition in a way words often fail to capture. Each portrait becomes a portal; each crack, a whisper from the subconscious.

In a time where perfection is filtered, polished, and pixelated, Simon Berger chooses to break the surface, quite literally, to uncover what lies beneath.

*Because sometimes, to truly see, we must first dare to shatter what blinds us.